American Sarpoma Sefa-Boakye discovered that she wanted to be a doctor at the age of nine. Born in southern California, the daughter of Ghanaian immigrants, she says that on her first trip to Africa for a funeral in her parents’ homeland she was moved by poverty.

“I thought one way to help would be to become a doctor,” Sarpoma, 39, tells BBC News Brazil.

When it came time to enter the medical school – which is offered in the United States as a graduate student – Sarpoma enrolled in American universities, but instead chose a less usual destination: the Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM) in the capital Cuban, Havana.

According to her, what weighed in the decision was the possibility to finish the course without debts, since the Cuban government offers scholarships to the American students.

“I thought, ‘Am I going to be able to afford a course in medicine in the United States, which costs between $ 200,000 and $ 300,000?'” He recalls.

Sarpoma is part of a group of 170 American doctors trained by ELAM, most of them black or Latino.

It may sound strange that citizens of a rich country like the United States participate in a program aimed at young people from low-income communities. But in American, Black and Latino colleges account for less than 6% of medical graduates.

“Most black and Latino students can not afford to pay for the medical course in the United States,” says Melissa Barber, a graduate of ELAM in 2007 and the coordinator of the program that selects American students for Cuban school to IFCO (Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization, in Portuguese), in New York.

In contrast, 47% of Americans trained by ELAM are black and 29% are Latino. In exchange for the free course, they undertake to work in areas lacking medical services when they return to their country.

Founded in 1999 to provide free education to young people from poor nations in Central America and the Caribbean affected by hurricanes Mitch and Georges, ELAM today brings together students from 124 countries.

The first Americans arrived in 2001 after leaders of Congressional Black Caucus, the group of black congressmen from the United States, visited the island and reported the shortage of doctors in some minority areas in their country. The Cuban leader at the time, Fidel Castro, offered scholarships to low-income Americans.

The selection of candidates is the responsibility of the IFCO, an institution that opposes the economic embargo imposed by the United States on Cuba. The final decision lies with ELAM.

“Every year, we receive 150 applications on average, of which about 30 actually enroll, and 10 are sent to Cuba,” says Barber.

The course lasts six years, two more than in the United States. There is also an additional year, at the beginning of the course, dedicated to preparatory classes focusing on science and Spanish.

Despite the tension in relations between the two countries, the ELAM-trained Americans guarantee that the program leaves politics out. “Some people think that students are going to be used as a political tool on both sides, but that’s not true, we’re only there to study medicine,” says Sarpoma.

Injections on the first day

The scholarship includes dormitory accommodation, three meals a day in the campus cafeteria, books in Spanish, a uniform and a small monthly financial aid.

Students are warned about “Spartan” accommodations, unlike what they are accustomed to in their country, and difficulties such as an occasional lack of energy and little access to the internet. But what most surprised Sarpoma was the method of education, focused on prevention and interactions with patients from the outset.

“In the United States, schools use actors to play the role of patients, not in Cuba, you learn in the clinic.”

Barber highlights the community aspect of the Cuban system. “Teams formed by a doctor and a nurse are responsible for a small geographic area, they know that community. Patients go to the clinic, and the professionals also go from house to house.”

In making the diagnosis, doctors are encouraged to consider biological, psychological, and social elements. “You are looking at the full picture, what is happening in the life of this patient, including social and environmental factors, that can cause these symptoms,” he says.

“If you need more care, there are polyclinics with all the specialties,” he says, noting that the patient will only go to the hospital if these two first steps are not enough to solve the problem. Barber compares this system to the American, where many do not have health insurance. “In the United States, often when they get to consult a doctor is case of emergency, no more prevention.”

Family medicine

To practice in the United States, doctors trained in Cuba must pass a series of examinations, as well as their colleagues trained in American schools. They must also complete a medical residency program in the United States.

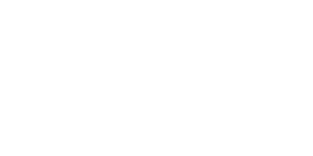

“The quality of education they receive is comparable to that of programs at American universities,” says the president of the National Medical Association (NMA) in the acronym in English), Doris Browne.

Founded in 1895, the NMA is the oldest association of black doctors in the United States and has among its objectives to improve the quality of health services for minorities and underprivileged communities in the country.

According to Browne, there are few trained doctors in the United States who are dedicated to primary care, which means there is a shortage of professionals in this area.

Despite being the country with the highest per capita spending on health, the United States lags behind Cuba in some health indicators. In 2016, according to the World Bank, the infant mortality rate (number of deaths per thousand live births) was 4 in Cuba and 6 in the United States. There is still great disparity related to race and depending on the state. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an agency of the US Department of Health, from 2013 to 2015 the infant mortality rate for children of white women ranged from 2 , 52 in the capital, Washington, to 7.04 in Arkansas. Among mothers of Hispanic origin, the rate ranged from 3.94 in Iowa to 7.28 in Michigan. Among blacks, from 8.27 in Massachusetts to 14.28 in Wisconsin.

In this context, the president of the NMA says that the work done by doctors trained in Cuba, who serve poor and minority areas, is “extremely important.”

“We need more family physicians working in these communities,” Browne points out.

Short time with patients

According to IFCO’s Barber, more than 91 percent of Americans trained by ELAM work in primary care. Sarpoma, who completed the course in 2009, is a family doctor in San Diego, California. She also works with the Birthing Project USA, which has projects around the US and the world to reduce infant and maternal mortality rates.

Among the difficulties of adaptation that he faced when returning to the United States, Sarpoma mentions the short time with the patients. “On the first day of my residency, I spent an hour with a patient, I did not realize that everyone was waiting outside, they called me slow, but I was just doing my job, you have to talk to the patient,” he recalls.

In the United States, the average time a physician spends with each patient is 15 minutes. “It’s very frustrating,” Sarpoma confesses.

She also says she has received little training to deal with some problems that are more common in the United States than in Cuba, such as overdoses and gunshot wounds. Another difference is the use of laboratory and imaging tests, much larger in the United States than in Cuba, where they are usually used only to complement the diagnosis.

Barber admits that there are those who distrust doctors trained in other countries. “There are some people with this mentality, with the idea that they are different, and therefore not as good as those trained in the United States,” he says.

“But in the communities where they work, they are always welcome, because they go where most American doctors do not go.”